- Home

- Thor Hanson

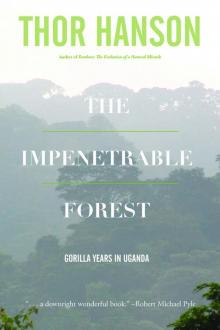

The Impenetrable Forest Page 10

The Impenetrable Forest Read online

Page 10

Of course, in many cases the melancholy need hardly be acted. Families often arrange marriages without the daughter’s consent, and young girls may find themselves paired with elderly men or complete strangers. Ugandan matchmakers place far more importance on haggling over the bride-price than in creating wedded bliss. The cost of a wife depends largely on the wealth (or perceived wealth) of the groom’s family, but the fees are always exorbitant. In Buhoma, young men complained constantly about their “dowries” and how to pay them off. The sum usually included between one and two hundred dollars in cash, supplemented with at least twenty goats, ten cows, and quantities of tonto, millet, and other commodities—far more than anyone could afford to pay at one time. Remittance often stretched over years or even decades, forming a complex network of debts between families and clans throughout the area.

The bride-price system plays an important cultural role in binding Bakiga communities together, but at significant cost to the social status of women. The hardship of long-term payment makes men more likely to treat their wives as property, particularly second or third spouses. As Agaba Philman, a porter who worked for John, once told me: “For twenty goats, she will wash my feet!”

Women carry out the brunt of agricultural and household labor for every Ugandan family, forming the backbone of village economies throughout the country. Local and international development groups recognize this fact, and women’s rights are slowly improving, but the pace of change slackens as you range farther from the influence of urban centers. Still, Dominico’s young daughter-in-law would have had far more to cry about in previous times, when meeting the male members of her new family involved sitting on a wooden stool puddled with their combined urine. After this symbolic ritual, any of them was free to demand sex.

“If a man came home to find his brother’s spear beside his door, it meant he was with the wife,” Enos Komunda had explained to me. “He could either wait or go directly to plant his spear at the brother’s house.”

A former park guide with a powerful voice and natural flair for storytelling, Enos had recently enrolled at the Anglican seminary in Kabale. We missed him at the park, and John and I both had some qualms about his new career choice. Corruption in the Church of Uganda allowed high-level clergy to live in luxury from the offerings of poor rural parishioners, and a suspicious number of their “local development” projects never made it beyond the fund-raising stage. Still, we had encouraged Enos to go and even agreed to help pay the school fees. Village life offered few opportunities for advancement, and we couldn’t begrudge him his chance for an education and a good job in the ministry.

For his independent research, Enos chose to study local religious and cultural traditions. He spent his school breaks interviewing elders around Buhoma, and we often talked at length about various Bakiga customs.

“For a woman, it was taboo to eat chicken,” he told me seriously one day as we bounced along toward Kabale in the back of Liz’s car.

“Sure?” This sounded interesting, and I prodded him for more. “Why? Was there a belief it could make them sick?”

“No, no.” Enos barked a laugh and shrugged. “It is because we men wanted to eat all the chickens!”

I laughed with him and he continued.

“The same was true for goats. Girls were allowed, but when they reached a certain age it became taboo. You know these intestines?” He made a braiding motion with his hands. “The sweet ones?”

I nodded. Throughout the region, tripe is considered a delicacy, and enterprising cooks braid the entrails into long ropy strands for a special stew.

“When a girl became too old, they filled the intestines with empazi. She bites it, the ants come out, and she never eats goat again!”

Thinking of it now, I shuddered and discreetly poked through my bowl of stew, relieved that Dominico hadn’t served me anything braided.

Also known as safari or fire ants, empazi travel in unstoppable, mile-long columns that have earned them a more sweeping title in the folklore of tropical Africa: army ants. One misstep in the forest and they swarm up your legs in an instant, biting simultaneously from a hundred different points, like tiny stabs from a rain of hot nails. More than once I’d seen guides, trackers, and even tourists frantically strip off their clothes to shake out the writhing hordes. Cultural symbolism aside, chomping down on a mouthful of empazi would be enough to spoil anyone’s appetite for goat. Or chicken. Or chocolate, french fries, lasagna, doughnuts—pretty much anything! In the United States, army ants could make somebody a fortune sold as a dieting aid.

Dominico invited me into his house for dinner, to a private room with a kerosene lamp, a table, and a setting for one. As a muzungu, I was often treated by people in the village with a kind of habitual deference left over from colonial times. My position of authority with the park added to their preconceptions, and many locals were shocked to see me engage in physical labor or eat from a common bowl. At social gatherings like Dominico’s, the host usually singled me out for special treatment, an honor that was complicated and awkward to refuse. Instead, I simply extended the invitation to other people at the party: two porters from the trail crew and Caleb Tusiime, a park guide who was training to become a nurse.

We ate quickly, talking and laughing by the lantern’s ruddy orange light. Someone called for another jug of tonto, and our conversation soon turned (as it would with any group of young bachelors in Buhoma) to the topic of dowries. I teased them, naming women from the village, and asking, “Mbuzi zingahi?”—“How many goats?” When I mentioned that we paid no bride-price in the States, they shook their heads in envious disbelief. “And,” I added, “the woman’s family even pays for the wedding party.”

“Is it?” Caleb’s laugh was high and drawn out, like the shout of a loon. “In America, I think I would be married many times!”

Later that night the clouds finally parted, ghosting away from a crescent moon like giant flat-bottomed boats. Walking home proved easy in spite of the tonto, with my path lit clear as midday by the glow of moon and stars. I paused outside my house and listened to the quilted echo of Dominico’s drums spill out across the valley. The rhythm was almost visible, a half-imagined mist, murmuring with cricket rasp as it drifted over the farms and treetops. I heard a wood owl call, and for an instant the forest seemed to resonate with silver-blue sound, its wet leaves throwing back moonlight like the pale shine of a thousand, thousand dimes.

Several days later, the trackers and I passed Dominico’s shamba on our way to the forest. He waved to us wearily, squinting through the smoke of his tiny wooden pipe, as if still hung over from the party. Next door, we found his neighbor, Kazungu, preparing beer for another village celebration.

“Agandi,baSsebo,” he greeted us, offering up a sample of his labors. We paused while he scooped a cup of brew straight from the hollow log where his youngest son was trampling ripe bananas. Draining off the frothy pulp, everyone tasted from the cup with thanks and nods of approval. Unfermented tonto is a sweet and surprisingly palatable juice called omubisi, favored by children and nondrinkers. We filled a plastic jug to take with our lunch and set off again, climbing rapidly toward the forest edge.

Katendegyere group’s trail led us along the steep southeastern flanks of Rushura, ascending gradually through a dim realm of canopied shade and pale branches, hanging down with vines. We found fresh sign and night nests near the Zairian border, and Charles bent down to examine the dung.

He flattened two piles with the toe of his boot, filling the air with a pungent, barnyard reek. Pointing out certain patterns of thin fiber in the bolus, he turned to me and shook his head with a rueful smile. “Again they are chewing bananas.”

We followed the gorillas’ trail into a steep-sided valley recently cleared for cultivation by Zairian farmers. Much of Katendegyere group’s former range had eroded over the past decade, as forested areas outside the park fell prey to the ax and the increasing demand for agricultural land. Nearly everything

on the Zaire side had been cut, and when we found the gorillas here, they were usually raiding banana shambas, making best use of the strange new trees that had suddenly sprung up in their backyard.

Today was no different, and from our vantage on the hillside we could see the gorillas clearly. Their dark shapes looked bulky and out of place in the fields, moving slowly between broad-leaved banana plants.

As we made our way down the slope, a farmer called out from the smoky doorway of his hut. We stopped to talk, and he came across the compound to meet us, reed thin and barefoot, with proud, aristocratic eyes that belied his tattered clothing and ramshackle home. One of our favorite shortcuts through the forest crossed this shamba, and on other days he had greeted us with gifts of passion fruit or omubisi. But now his eyes were cold, and he raised his voice in an angry shout: “Your animals, they are bleeding us! What will we eat now?”

I tried to reassure the man but knew that compensation for his loss would be a long time in coming. The park and IGCP offered a small “token of appreciation” to farmers with gorilla-damaged crops, but the system was new, and we didn’t have permission from Zairian authorities to compensate people on their side of the border. Mishana James stayed behind to explain things, while Charles, Prunari, and I descended the hill and positioned ourselves near the feeding apes.

We watched the group’s second silverback reach up with one huge arm and pull down a fifteen-foot tree. I cautiously snapped pictures, but he seemed indifferent to the camera, glancing our way with placid eyes and scratching absently at the long black fur on his shoulder. Then, with a casual flex and a sideways tear of his teeth, he separated the trunk into ropy strands and began chewing noisily.

Bananas are the only local crop favored by gorillas, but contrary to popular belief, they rarely eat the fruit itself. The cartoon image of an ape peeling fistfuls of yellow fruit is the product of zoos and circuses, where caged animals develop a taste for whatever their keepers feed them. In the wild, it’s actually the watery core of the plant stem that draws them from their forest home. Stands of banana trees like this one, planted near the forest edge, may be destroyed long before the farmer ever has a chance to harvest.

We sat quietly while the silverback wrenched down another tree. He positioned himself between the two fallen stems like a choosy diner in a buffet line, alternately yanking mouthfuls of wet fiber from one and the other. Prunari leaned forward and whispered a name in my ear, “Mutesi”— Rukiga slang for a lazy, spoiled child. I hastily sketched his nose print while occasional belches and rustling leaves revealed the presence of other apes resting and feeding around us. We couldn’t see them, but we knew who was there: Mugurusi, “Old Man,” the shy lead silverback; Nyabutono, “Little Lady,” his constant companion; or Karema, “Cripple,” the calm young female with maimed fingers. Our sightings of the group had improved dramatically in recent weeks, and I felt we were coming to know this family of apes by their personalities as well as their physical traits.

So when we heard a series of sharp pig grunts in the tall shrubs beside us, we looked at each other with immediate smiles: “Makale.”

Pugnacious and slightly too young to challenge the group’s three adult silverbacks, Makale was a growing black-backed male and the group’s self-appointed watchdog. He served as our barometer for judging the group’s mood, a surly pressure vent for any kind of tension or collective nerves. But while Makale’s grouchy personality had become almost endearing, his habit of screaming and charging to within inches of us exposed him—and the rest of the group—to a variety of dangerous human diseases. Gorillas share 98 percent of the same genes as Homo sapiens and can succumb to the same viruses and bacteria that make us ill, as well as many more that we carry unknowingly. We followed the park’s health and minimum-distance regulations with vigilance, but convincing a charging gorilla to observe the same rules is another matter altogether. Today, however, feeding on a large banana stem demanded all of Makale’s attention, and we didn’t see more than the dark shadow of his glare, deep within the bracken.

The farmer above us had returned to work, swinging his hoe at the earth and turning back the soil for a row of young banana shoots, as if in a conscious race to offset every tree the gorillas had devoured. This convergence of forest, wildlife, and agriculture encapsulated the conflict between population growth and dwindling natural areas. Although fields like this one had been vital gorilla habitat five years earlier, it was difficult to blame the loss on any individual. People living in such a remote valley were among the poorest in Central Africa, struggling at the lowest levels of subsistence. Of course the farmer was angry; any crop damage on this steep, marginal land meant an immediate loss of food for his family.

Gaining the support of local people presents one of the fundamental long-term challenges for Bwindi Impenetrable Forest. When the park was created in 1991, thousands of villagers found themselves suddenly cut off from a traditional source of bush meat, firewood, timber, and medicinal herbs—their customary habits stopped for the sake of international tourists and an animal that raided their crops.* Starting from this setback, park managers attacked the public relations problem with a combination of experimental policies.

Communities surrounding the forest were invited to elect representatives to a park advisory committee, ensuring local input in major management decisions. Their suggestions helped the park establish multiple-use zones along the forest periphery, and begin licensing designated herbalists from each village to organize a controlled, sustainable harvest. Beekeepers were also given limited access, and certain communities resumed the collection of raffia palms for traditional weaving and basketry. Many of these programs were administrated with the help of Development Through Conservation (DTC), a CARE International program working on conservation education, family planning, and agricultural development in communities bordering Bwindi and Mgahinga.

The multiple-use program went ahead with relative ease, but controversy surrounded the centerpiece of Bwindi’s community-development efforts, a plan to distribute portions of tourism-generated revenue directly to local villages. Communities would submit funding proposals for their own projects, avoiding the typical top-down approach of government-sponsored development. Early ideas in Buhoma ranged from a new roof on the primary school to road improvements or equipment for the medical clinic.

Most park managers and local officials supported the goal of revenue sharing: helping people associate gorillas and forest conservation with a tangible increase in their standard of living. Contention arose over the two major points of implementation—how much to share and how to share it. Could a park system that already relied on foreign aid to balance its books really afford to give anything to villagers? Conservationists had watched similar programs struggle in Kenya, where project after project failed due to the logistics and politics of distributing money at a local level. Bwindi’s program hoped to avoid these pitfalls, ensuring accountability by allowing community representatives to choose which of their own projects to fund. Additionally, the World Bank would share administrative costs and guarantee a steady income through its new Bwindi Trust, a special account to support park management, research, and community development in perpetuity. In any form, revenue sharing represented a new concept for Uganda’s national parks. Bwindi’s attempt was the pilot study to determine whether headquarters would implement a countrywide program.

Before heading home, we advanced slowly toward the gorillas, trying to coax them back into the forest. After such a calm day, I hated to risk disturbing the group, but leaving them alone in the fields only invited worse treatment. When we were gone, the farmers would begin to shout, beat on pans, and throw rocks—a good technique for driving gorillas from your shamba but a serious setback to our habituation efforts.

Veils of rain drifted over us, and most of the gorillas had already retreated into a bower of heavy shrubs, but Mutesi was still feeding as we approached. He stared at us warily and began chewing faster, the pithy juice

running sloppily down his chin. He was obviously nervous but still appeared to relish every bite. For Katendegyere group, the sheer epicurean pleasure of a fresh banana stem seemed to outweigh any risks involved in raiding the shamba. I doubt that even the old Bakiga stuff-the-food-with-empazi trick would have slowed them down. Mutesi certainly looked like it would take more than a mouthful of army ants to move him from his feast. But we kept edging forward and finally he gave way, disappearing into the forest with a tattered banana tree dragging from his fist, like the last-minute spoils of a Viking raid.

That evening, a late cloudburst hammered the eaves of my house, drumming against the banana thatch like endless, padded applause. I went to bed early, listening to raindrops leak through the roof and rattle into my ragtag collection of pots and basins in a cheap, tin echo of the fading storm. If the rain continued, I knew the park staff would be short-tempered in the morning. No one in Buhoma slept well when they spent half the night shifting their bed around the house, trying to avoid the constant indoor drizzle of a sodden thatched roof. Ephraim and James Kawermerwa had recently patched my bedroom ceiling, and I felt a little smug as I drifted off in leak-free comfort.

Sometime later, a new sound in the house brought me slowly back to consciousness. The rain had stopped, but there was something else, a subtle noise pervading the blackness around me. I listened carefully as I came awake but couldn’t pinpoint the source. It seemed to come from all sides and sounded like…seething. It can’t be ants, I told myself with a nervous mental chuckle. You can’t hear ants. Go back to sleep. But the skittering racket continued to grow, and rest was impossible until I settled the mystery.

Lighting a match in the rain forest wasn’t always a simple task, but it had never seemed to take longer as I scratched through half a box of damp sticks. Finally, a light flared up, and I glimpsed something that made me wish I’d never opened my eyes: empazi, millions of them, blanketing the walls, covering the floors, dropping from the ceiling, and swarming up the bedspread toward me in a teeming mass.

The Impenetrable Forest

The Impenetrable Forest